Wealth Tax in Switzerland

Switzerland, famous for its stunning Alpine landscapes, world-class chocolates, and precision engineering, has long been a magnet for global business and finance. Its central location in Europe, coupled with a reputation for political neutrality and financial security, makes it a top choice for expatriates and high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs) seeking opportunity and stability. However, did you know that where you live in Switzerland could significantly impact your wealth tax? How is it calculated, and what does it mean for your assets? In this post, we’ll delve into the entire landscape of Switzerland’s wealth tax system. Whether you’re new to Switzerland or considering a move within the country, gaining a thorough understanding of these aspects is essential for effective financial planning and ensuring compliance with local regulations.

Wealth Tax Law

Switzerland operates under a three-level tax system, where taxes are levied at the federal, cantonal, and municipal levels.

Federal

At the federal level, taxes are designed to be applied uniformly across the entire country, meaning the same tax rules apply everywhere, even though the rates might vary based on specific criteria. These include direct taxes like income tax, which is directly tied to your earnings, and indirect taxes such as value-added tax (VAT), which is applied to goods and services.

Cantonal

Although wealth tax in Switzerland is classified as a direct tax because it directly relates to taxable net worth, it is not imposed at the federal level, unlike in many other countries. Instead, the authority to levy wealth taxes was entrusted to the cantons by the Swiss Confederation and is codified in Article 2 of the Federal Law on the Harmonization of Direct Taxes (StHG).

Municipal

At the third level, municipalities typically apply a percentage of the cantonal tax. These municipal rates are often adjusted to reflect the specific financial needs of the community, such as funding local infrastructure, education, and public services.

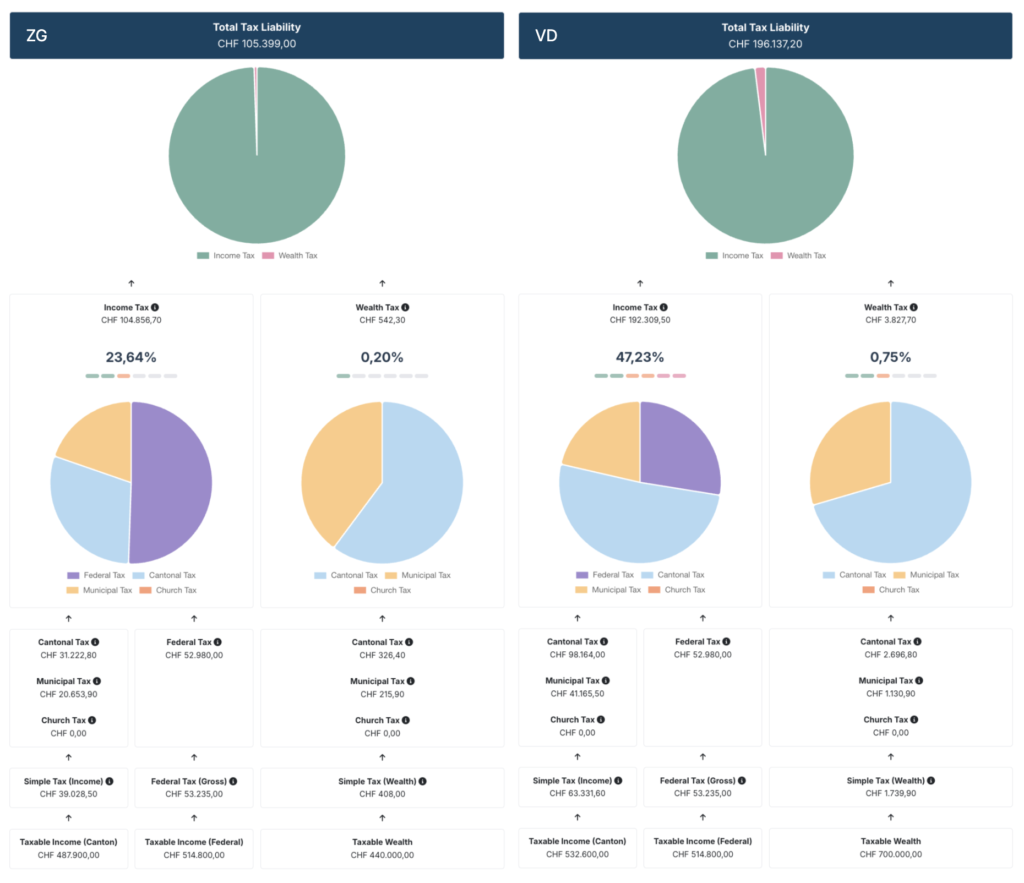

As a result, your wealth tax bill combines contributions from both your canton and municipality, with the amount varying significantly based on your place of residence. The graphic below illustrates the tax situation of a married couple with one child living in either Zug (canton of Zug) or Montreux (canton of Vaud) under identical financial circumstances. For instance, although the federal income tax remains the same regardless of residence, the overall tax liability differs significantly.

👨👩👧 Family Status: Married with 1 child

🏡 Residence: Zug (ZG) or Montreux (VD)

💵 Combined Net Income: CHF 550,000

💰 Wealth: CHF 700,000

It is worth noting that, although income tax constitutes the majority of the overall tax burden in both regions, the disparity in wealth tax is proportionally even more pronounced. Precisely, at this level of wealth, Vaud’s wealth tax is approximately seven times higher than that of Zug, whereas the income tax is only twice as high. This significant difference arises due to the high deductions offered by the canton of Zug, resulting in differing starting points for calculation. Additionally, the tax rates themselves vary between the two cantons.

Swiss Wealth Tax by Canton

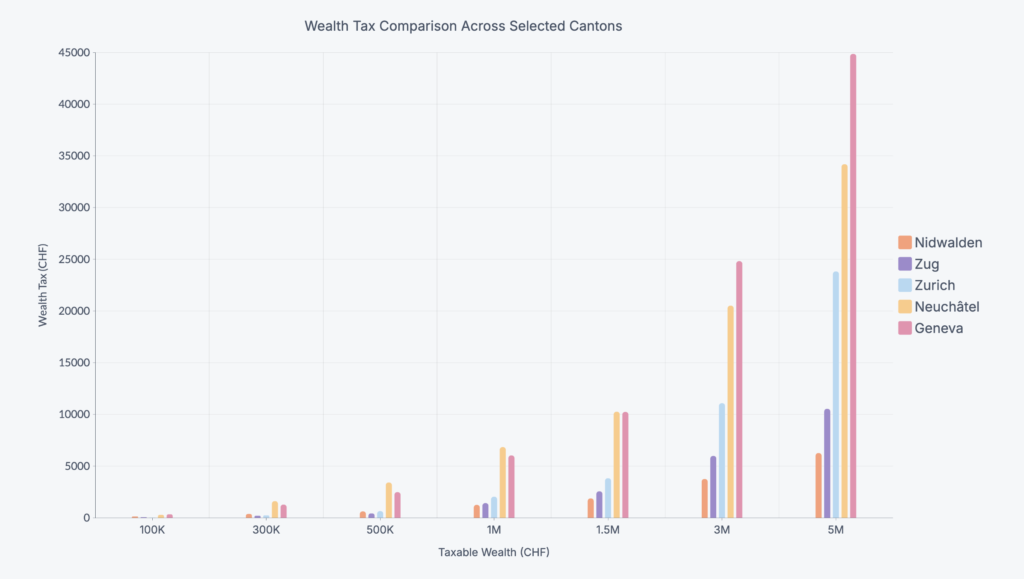

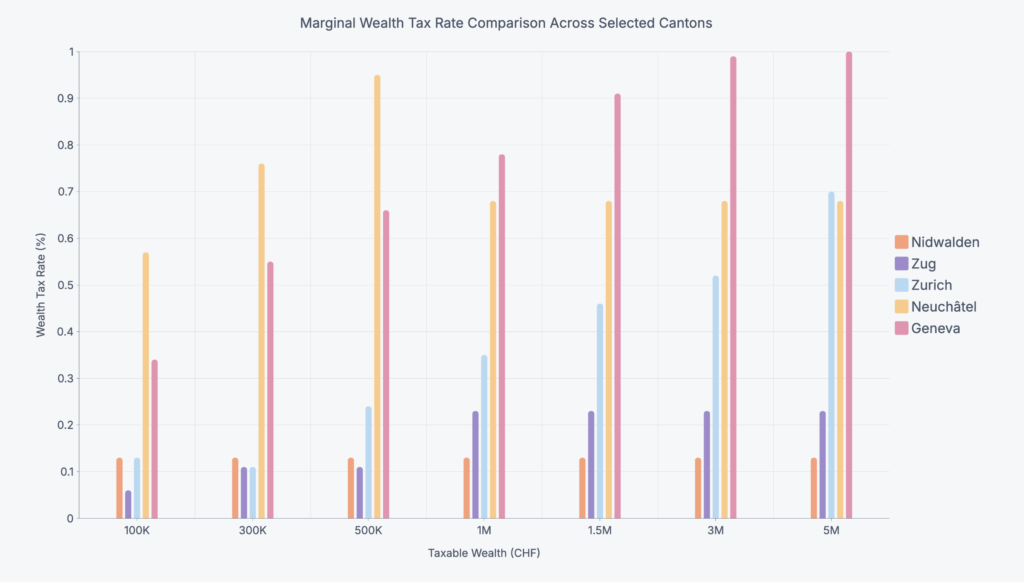

The following tax diagrams illustrate the cantonal wealth tax amounts and marginal rates for a single individual across five cantons in Switzerland, assuming a consistent financial situation for comparison purposes.

Nidwalden Wealth Tax: The Simplest and Cheapest Option

Nidwalden offers the simplest wealth tax system among the cantons, applying a constant tax rate on taxable wealth. More importantly, Nidwalden stands out for its exceptionally low tax burden, making it one of the most cost-effective cantons.

Geneva and Neuchâtel Wealth Tax: High Tax Burdens with Different Approaches

Neuchâtel starts off with a higher tax burden, particularly in the earlier stages of wealth accumulation. The canton’s tax rate increases rapidly, making it more expensive at lower wealth levels. However, as wealth grows, Neuchâtel stabilizes its tax rate.

Geneva, in contrast, not only begins with a relatively high tax rate but continues to increase the rate as wealth grows. This makes Geneva particularly expensive for those with considerable wealth. While both cantons impose a significant tax burden, the key difference lies in their progression—Neuchâtel’s rate stabilizes, whereas Geneva’s continues to rise.

That said, Geneva’s wealth tax is subject to a cap under Article 60 LIPP, known as the “bouclier fiscal.” Legally, the wealth tax will be reduced if the combined tax burden from income and wealth taxes exceeds a certain threshold of net taxable income. This rule primarily benefits individuals with low income relative to their wealth, especially when minimal or no taxable earnings are generated from investments. Such provisions can slightly alleviate the financial impact for certain taxpayers, although Geneva’s overall tax structure remains steep for high-net-worth individuals

Zug and Zurich Wealth Tax: More Favorable Tax Conditions

Compared to Geneva and Neuchâtel, Zug and Zurich offer more favorable tax conditions. Both cantons impose lower tax rates, making them much cheaper options for the same levels of taxable wealth.

Municipal Wealth Tax Differences

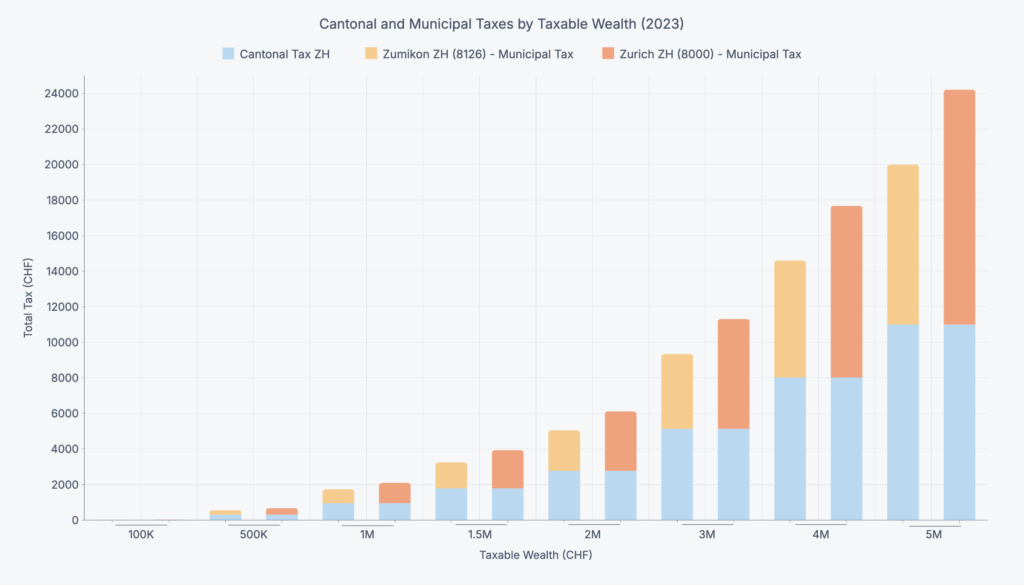

The following tax diagram illustrates the municipal wealth tax amounts for a single individual in Zurich, with a comparison between two different municipalities: Zumikon, a municipality close to Lake Zurich, and the City of Zurich.

Municipal tax calculations are derived from a shared cantonal tax. In the canton of Zurich, for the 2023 tax period, municipal tax rates for individuals range from 72% to 130% of the shared cantonal tax. Here, in our example, Zumikon applies a rate of 82%, while the City of Zurich applies 120%, leading to noticeably different wealth tax burdens at the municipal level.

Paying Wealth Tax

In Switzerland, wealth tax is declared as part of the annual tax return, where assets subject to wealth tax are divided into distinct sections for movable assets, like bank accounts and investments, and immovable assets, such as properties. Wealth tax is then calculated on the total value of these assets after deducting any applicable liabilities, such as mortgages.

Who Pays Wealth Tax?

Swiss resident individuals are subject to wealth tax on their worldwide assets, known as unlimited wealth tax liability. You are considered a Swiss resident individual if you meet any of the following criteria:

- You have your domicile in Switzerland; or

- You spend, without significant interruption, at least:

- 30 days in Switzerland for work purposes; or

- 90 days in Switzerland for non-work purposes.

Is Wealth Tax Payable Every Year?

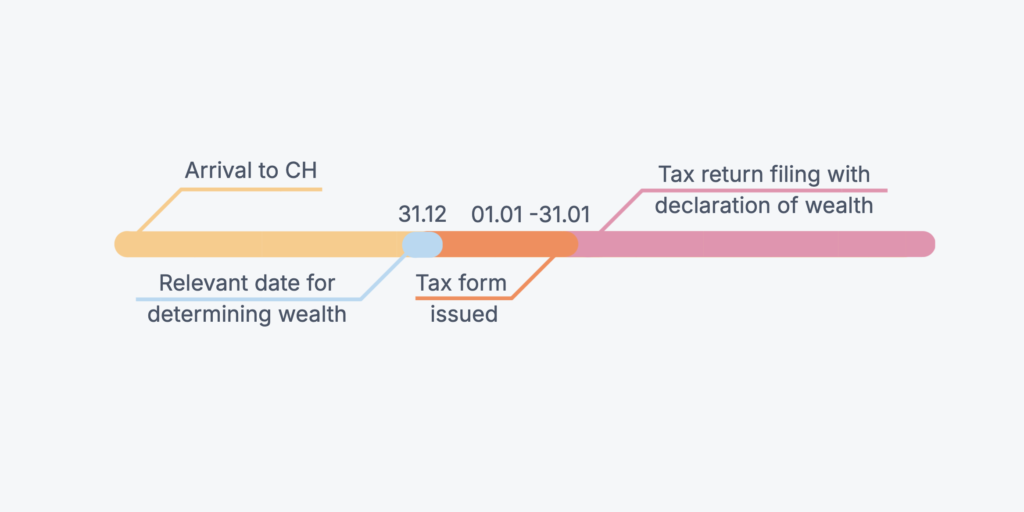

Wealth tax in Switzerland is assessed annually and is based on your taxable net worth as of December 31st. If you arrive or depart during the year, the tax is due from the first day of residency until the end of that residency and is levied on a pro rata temporis basis.

Where is Wealth Tax Payable?

Article 2 of the Federal Law on the Harmonization of Direct Taxes (StHG) grants each canton autonomy over how wealth taxes are assessed and collected. Therefore, responsibility for levying these taxes lies with the canton of the taxpayer’s primary residence, or, if the taxpayer owns real estate, with the canton where the property is located.

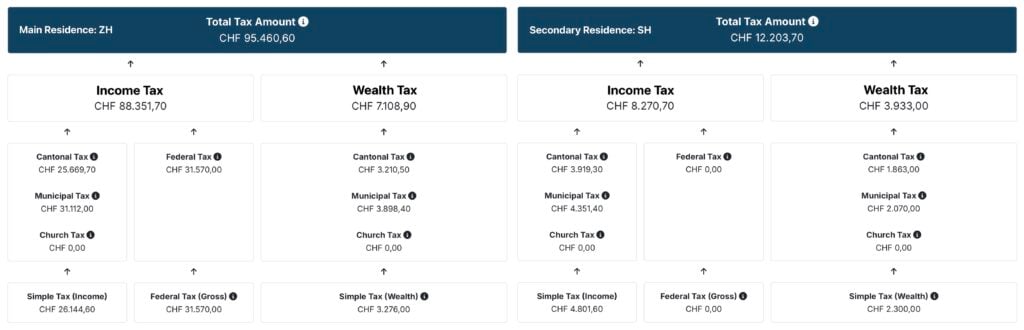

In practice, this means that owning real estate can establish tax residency without the property owner’s physical presence. This applies both to international taxpayers and to those living in Switzerland but residing in a different canton. The Taxolution Portal Calculator below illustrates a scenario in where a household resides in Zurich while owning property in Schaffhausen. In this case, the majority of their income and assets will be taxed in Zurich. However, they must also file a separate tax return in Schaffhausen to account for taxes in that canton. To streamline this process, a copy of the Zurich tax return can often be submitted to meet the filing obligation in Schaffhausen. Swiss tax laws include clear provisions to prevent double taxation of income and wealth across cantons, ensuring taxpayers are not unfairly penalized for multi-canton ownership.

👨👩👧👦 Family status: Married with no children

🏠 Residence: Zurich (primary residence)

🏡 Property: Schaffhausen (secondary as a seasonal residence)

💵 Income: CHF 350,000 in total, derived from CHF 300,000 in Zurich and CHF 50,000 in Schaffhausen

💰 Wealth: CHF 3,000,000 in total, comprising CHF 2,000,000 in Zurich and CHF 1,000,000 in Schaffhausen

As illustrated in the graphic above, tax obligations are distinctly divided between Zurich and Schaffhausen. Zurich, as the canton of primary residency, has the authority to tax all income and wealth, except for the income and value specifically associated with the secondary property located in Schaffhausen. This arrangement arises because owning a secondary residence creates a secondary tax liability, allowing the canton where the secondary property is located to impose its own taxes. The tax rates for both income and wealth are calculated based on the combined totals from both cantons and are generally aligned, with each canton taxing its respective share. Lastly, it’s worth noting that federal taxes are paid exclusively in the canton of primary residency.

Can I Pay Wealth Tax Online?

The simple answer is yes. In most Swiss cantons, wealth tax return can be submitted online, as digital tax return submission is available through official portals. However, none of the cantons provide a full online portal and platform with detailed account balances or open invoices. To address this shortcoming, our service provides a centralized platform, Taxolution Tax Portal, that enables you to maintain a clear and organized overview of your tax situation.

After submitting your tax return online, the tax office conducts an assessment. This assessment is considered final unless contested within the specified deadline. Following the assessment, a final invoice is issued, sometimes together with the assessment, reflecting any balance due. In the case where prepayments, such as provisional invoices or withholding taxes, exceed the total liability, the invoice will then show a credit in favor of the taxpayer.

Finally, It is worth noting that in Switzerland, a single tax return must be submitted annually, covering income and wealth taxes at all three levels: federal, cantonal, and municipal. Wealth tax itself is not billed separately; it is combined with income tax at both the cantonal and municipal levels. As for payments, taxpayers can use e-banking systems or opt for traditional methods, such as paying in cash at the post office counter.

Wealth Tax and Assets

All of a taxpayer’s assets, both domestic and foreign, must be declared in the tax return for wealth tax purposes. While foreign assets are not directly subject to wealth tax, they are still considered when calculating the applicable tax rate. Since wealth tax is assessed on net wealth, it is equally important to declare any debts, such as mortgages or loans, to accurately reflect the net value.

The Market Value of Assets

Assets are typically valued at their fair market value, which reflects the price they could obtain in a sale. For frequently traded assets, like listed securities, commodities, and cryptocurrencies, determining this value is straightforward. However, for tangible assets such as real estate, the fair market value often requires estimation. To ensure a comprehensive tax declaration, it is essential to report all taxable assets.

Types of Assets

In Switzerland, various types of assets subject to wealth tax are treated differently based on specific tax regulations and practices. This section outlines the key asset categories included in Swiss wealth tax calculations.

Wealth Tax on Property

Property values in Switzerland are determined by cantonal tax authorities and are often conservatively assessed, typically below actual market value. As a result, taxpayers often benefit from lower wealth tax liabilities compared to what they would face if properties were taxed at full market value. Furthermore, this comes with a greater stability in tax planning, as assessed values are less affected by market fluctuations.

Do I Have to Pay Wealth Tax on Foreign Property?

No, foreign properties are considered solely for determining the wealth tax rate but are exempt from actual taxation in Switzerland. This means that, while the value of foreign properties is not subject to Swiss wealth tax, it is included in calculating the progressive tax rate applied to taxable wealth within Switzerland. Additionally, to assess the Swiss tax value of foreign properties, pragmatic methods are generally used, such as estimating market value, using the tax value assigned in the property’s country of location, or adjusting the purchase price with deductions when it provides a reliable estimate of market value.

Wealth Tax on Swiss Property with Split Ownership

In Switzerland, wealth tax is levied based on the share of the property each individual owns. Each co-owner is only liable for the portion of the property they legally own or control. The value of the property is split according to the ownership percentages, and each owner declares their respective portion in their wealth tax return. In the case where the ownership is divided equally or unequally, the wealth tax will duly reflect the proportional ownership of each party.

For example, if two people co-own a property, each would report half of the property’s tax value in their tax return unless a different ownership ratio applies. This is especially common in inheritance cases where multiple heirs jointly own a share of the property as part of a community of heirs.

Wealth Tax on Cars

For luxury cars, including classic and sports cars, their worth is typically determined by the market or sales value, which can vary depending on factors such as rarity, condition, and demand. Classic cars, in particular, may appreciate in value over time, making them a more complex item to assess for tax purposes.

For standard cars that naturally lose value over time, the tax value is determined using depreciation formulas based on the car’s purchase price and age; therefore, their assessed value for wealth tax purposes decreases each year.

Leased cars are excluded from wealth tax calculations, as ownership remains with the leasing company. For the same reason, leasing payments are not deductible for tax purposes, so leased cars fall entirely outside the scope of Swiss tax returns.

Wealth Tax on Gold and Precious Metals

Gold, other precious metals, jewelry, and gemstones are considered taxable assets in Switzerland and must be declared in your wealth tax return. Their value is determined based on the market price as of December 31 of the tax year. To facilitate accurate reporting, the Federal Tax Administration publishes official tax values for these items annually on January 1. Taxpayers can reference these lists to ensure compliance with the required valuations.

Wealth Tax on Shares, Bonds, ETFs, and Investment Funds

Whether you hold shares in Swiss or foreign companies, they are all subject to wealth tax for Swiss tax residents.

The valuation of publicly traded shares is straightforward, as market prices are readily available as of December 31 of the tax year. However, the valuation of employee participation plans is subject to special rules.

For unlisted shares, where fair-market value cannot be directly assessed, the market value is usually determined using the “practitioner’s method.” This method considers two main factors: the value of the company’s assets after liabilities and the company’s average profits from recent years.

Wealth Tax on Unrealized Gains

If you own assets such as shares, property, or other investments that have appreciated in value but have not been sold, resulting in unrealized gains, you are still required to declare the current market value of these assets in your wealth tax return. The increased value of these assets will contribute to your total taxable wealth.

Wealth Tax on Pension Funds

Assets held in pension funds are generally exempt from wealth tax, including those in occupational benefit schemes (pillar 2) and tied private pension schemes (pillar 3a). These assets are not considered part of your taxable wealth as long as they remain within the pension fund. Non-Swiss pension fund assets are also usually exempt, provided their characteristics are reasonably comparable to those of Swiss pension funds.

Wealth Tax on Miscellaneous Assets

It is important to note that various other types of wealth must also be declared for tax purposes. These include:

- Life insurance policies with surrender value

- Investments in cryptocurrencies

- Shares in accounts of condominium and homeowners’ associations

- Crowd-investments

- Loans given to others

- Shares in undistributed inheritances

- Being a settlor or beneficiary of trusts

- Art, cars, antiques, or collections (e.g., wine) of significant value

- Intellectual property

- Large amounts of cash, regardless of currency

- Livestock (e.g., racing horses or farm animals, but not pets like hamsters, cats, or dogs)

However, standard household goods are exempt from wealth tax.

Swiss Wealth Tax vs. Other Forms of Taxes

In Switzerland, wealth taxes often stand apart in the broader spectrum of taxation systems. Unlike other forms of taxation, which focus on income, transactions, or specific assets, wealth taxes target the accumulated net worth of an individual or entity. Let’s delve into the key differences between wealth taxes and other major forms of taxation commonly encountered in Switzerland.

Wealth Tax vs. Capital Gains Tax

The taxation of capital gains—the positive difference between the purchase price and the sales price—depends on the type of asset and, in some cases, the length of ownership.

Securities

Capital gains from the sale of privately held securities—such as free-floating shares without a significant ownership stake, bonds, ETFs, investment funds, and cryptocurrencies—are generally tax-free for individual investors in Switzerland. However, if tax authorities classify an individual as a professional securities trader, these gains become taxable. Those who trade intensively in securities or other tangible or intangible assets in their own name should seek professional tax advice to ensure compliance and proper tax planning.

Real Estate

Capital gains from the sale of real estate are instead taxable in Switzerland. Despite the tax rate being progressive, it decreases the longer the property is held, incentivizing long-term ownership.

Wealth Tax vs. Gift Tax & Inheritance Tax

On one hand, gift tax is typically paid by the recipient and is levied at the time of asset transfer. While wealth tax is a recurring annual obligation, gift tax is event-driven and influenced by the relationship between the donor and recipient, with higher rates often applied to non-family members.

On the other hand, inheritance tax is a one-time tax applied when assets are passed on after death. The tax is usually paid by the inheritors, and the rate varies by canton. Generally, direct descendants, such as children, are taxed at a lower rate or may be completely exempt, while non-family members often face higher rates.

It is worth noting that in Switzerland, there is currently no inheritance or gift tax at the federal level; hence, each canton has the autonomy to decide whether to levy these taxes. As a result, significant differences exist across cantons.

For example, the cantons of Schwyz and Obwalden impose neither an inheritance nor a gift tax, while the canton of Lucerne only levies an inheritance tax. In contrast, the cantons of Vaud and Neuchâtel impose inheritance and gift taxes on asset transfers to descendants.

Wealth Tax vs. Income Tax

In Switzerland, income tax is levied at both the federal and cantonal levels, with rates varying based on your annual earnings. It is charged on income you earn from sources such as salary, business profits, and taxable investment income like dividends or interest (e.g., from savings accounts or bonds). While capital gains might seem like income, gains from selling specific assets, such as stocks or other securities, are generally tax-exempt for private investors.

In comparison, wealth tax is based on the value of what you own, while income tax is based on what you earn. Wealth tax is a recurring annual charge on your assets, while income tax is calculated each year based on your earnings.

Wealth Tax vs. Property Tax

Property tax is tied specifically to the full value of real estate and is collected annually in about half of the cantons in Switzerland. The tax ranges from 0.02% to 0.3% of the estimated property value, and the responsibility falls on the owners or co-owners registered in the land register.

In contrast, wealth tax requires property to be declared as an asset on your tax return, but unlike property tax, you can deduct any related debts.

Wealth Tax vs. Progressive Tax

While progressive tax isn’t a distinct type of tax, it describes a system where tax rates increase as the taxable amount rises. In Switzerland, income tax follows a progressive structure, meaning those with higher incomes pay a higher tax rate on their earnings.

Similarly, in Switzerland, most cantons apply a progressive wealth tax rate, meaning that as your total taxable net assets increase, they are taxed in higher brackets, with each range of assets subject to progressively higher rates. Once a certain threshold is reached, the tax rate caps at a maximum and no longer increases.

Wealth Tax around the World

Wealth tax is a topic that generates significant debate among policymakers, economists, and taxpayers across the globe. While some countries see it as a fair way to redistribute wealth and fund public services, others view it as a hindrance to entrepreneurship, innovation and long-term growth. Over the years, many nations have implemented, modified, or abolished wealth taxes based on these considerations. Changes to the wealth tax often affect another aspect of taxation: the inheritance tax. From the perspective of tax authorities, wealth taxes provide consistent and predictable annual revenue, whereas inheritance taxes, levied once per generation, result in more sporadic and unpredictable revenue streams. In practice, in most countries, it is common to impose either a wealth tax or an inheritance tax, but not both.

Which Countries still Have Wealth Tax?

Among OECD countries, only four still impose a wealth tax: Colombia, Norway, Spain, and Switzerland. In fact, many OECD countries that once had wealth taxes decided to repeal them over the last three decades. For example, Austria repealed its wealth tax in 1994, followed by Denmark and Germany in 1997, and the Netherlands in 2001. In the years leading up to the global financial crisis, several other European nations also moved away from wealth taxes. Finland, Iceland, and Luxembourg all abolished their wealth taxes in 2006, and Sweden followed suit in 2007. France was the last major EU country to reform its wealth tax in 2018, replacing it with a real estate wealth tax, signaling a shift toward taxing specific assets rather than overall wealth. However, while the focus appears to be shifting away from taxing accumulated wealth over time, it has concentrated instead on taxing wealth transfers between generations. Many of these countries impose substantial inheritance taxes, even on transfers to spouses and children, often with relatively low tax-free thresholds.

While many European countries have moved away from wealth taxes, the debate continues in other parts of the world, most notably in India and in the United States.

In India, the wealth tax was introduced in 1957 but abolished in 2016. It applied a 1% tax on assets above INR 3 million (approx. EUR 34,000), including “non-productive assets” like real estate, vehicles, and jewelry, and was levied on worldwide assets. The tax was abolished primarily to simplify the tax system and reduce the high costs of collection, which outweighed the revenue generated. However, following the abolition, income tax was made more progressive to compensate for the fiscal loss.

During the 2020 United States presidential race, Democratic candidates Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren both proposed highly progressive wealth taxes aimed at the ultra-wealthy. Sanders’ plan, for example, started with a 1% tax on net wealth above USD 32 million, with rates increasing up to 7% for fortunes exceeding USD 5 billion. However, wealth tax proposals have not gained traction under Joe Biden’s administration, and the topic has quieted in recent years. This trend is likely to prevail with the incoming Trump administration, as it is expected to focus on tax cuts rather than wealth taxation. Consequently, it is unlikely that a wealth tax will be considered in the near future.

Wealth Tax in Other EU Countries

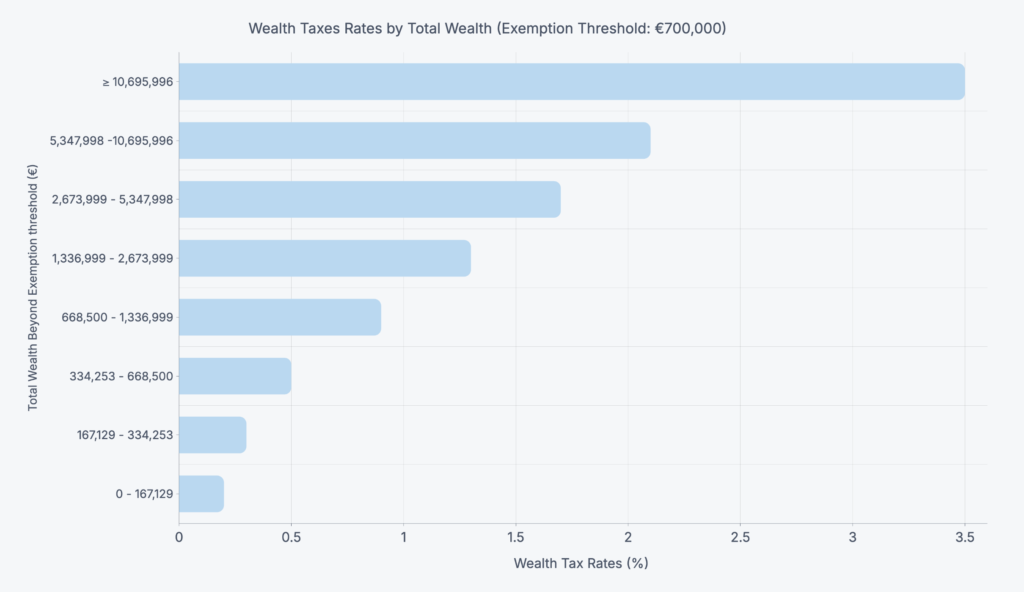

Spain’s wealth tax is similar to Switzerland’s in that both have regional variations—Spanish wealth tax rates differ widely between different regions, just as Swiss wealth tax rates vary between cantons. However, Spain imposes a nationwide threshold of €700,000 in taxable assets, with an additional €300,000 exemption for primary residences, which can be combined for married couples. In contrast, Switzerland allows for property mortgages to be deducted from the taxable assets, rather than offering a fixed allowance as seen in Spain.

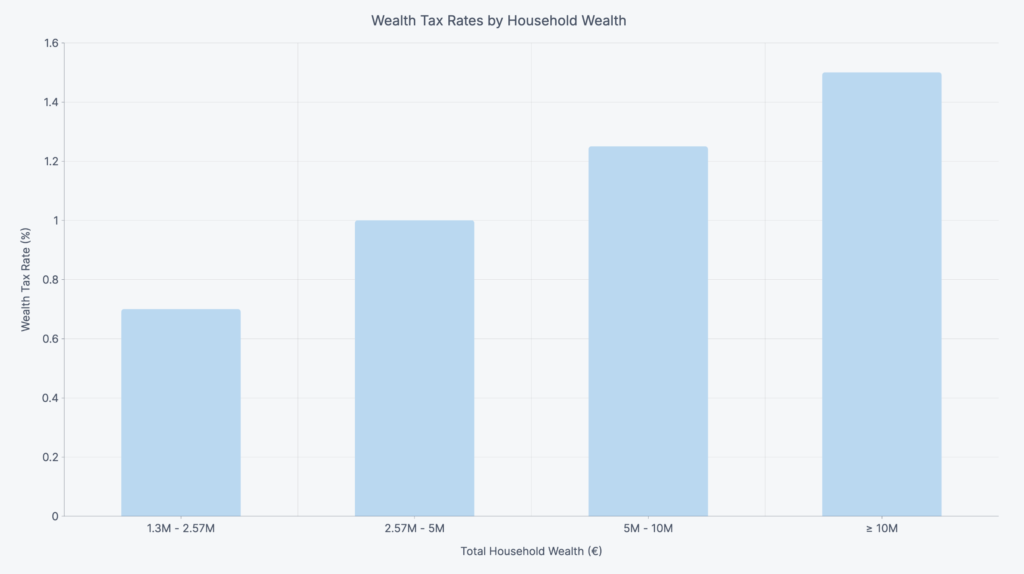

France’s wealth tax, reformed in 2018, now applies exclusively to real estate assets valued over €1.3 million, and it is payable by all households residing in France on their worldwide real estate holdings. Non-residents are only taxed on French properties exceeding this threshold. Prior to 2018, the wealth tax was broader, covering additional assets such as savings, vehicles, and jewelry, but the current system focuses solely on real estate. A key difference between the French and Swiss systems is that the French wealth tax is levied on households rather than individuals, meaning the combined assets of spouses or partners and any children under 18 are taxed together. In Switzerland, while wealth tax is generally assessed at the individual level, married couples have their assets combined and are taxed as a single entity.

Wealth Tax & Double Taxation

Double taxation occurs when the same income is taxed twice, typically in two scenarios.

The first is at the corporate level, where a corporation pays tax on its earnings, and shareholders are taxed again on dividends received from those earnings.

The second scenario occurs internationally—or, in Switzerland’s case, nationally between two cantons—when a taxpayer earns income in one jurisdiction but resides in another, with both claiming the right to tax the income.

This issue is particularly relevant for expatriates and high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs), who may face tax obligations in both their home and host jurisdictions.

In Switzerland, double taxation is addressed at both international and national levels. Internationally, double taxation treaties are used to prevent tax overlap, while inter-cantonal double taxation is prohibited under Article 127 of the Federal Constitution and resolved by the Federal Supreme Court in case of conflicts.

To date, Switzerland has established over 100 double tax treaties with other jurisdictions. These treaties generally follow the OECD Model Convention, utilizing the exemption method and the credit method to eliminate double taxation.

Wealth Tax Exemption

Wealth tax exemptions provide relief by excluding certain assets or income from taxation. In most Swiss cantons, wealth tax is only levied above a certain exemption threshold, often referred to as a social deduction. Additionally, the progressive tax rate ensures zero taxation on the initial portion of wealth. While the wealth tax base is broad—covering all assets, including those held abroad—certain assets, such as household goods, personal items and pension wealth, are usually exempt.

Wealth Tax Exemption Limit

Across Switzerland, eight cantons use flat-rate systems, where the same tax rate applies to all taxpayers once their wealth exceeds the exemption threshold. However, the canton of Nidwalden is a unique case within this system, as it does not have an exemption level. Instead, Nidwalden applies a flat rate of 0.0665% on all taxable wealth, making it the canton with the lowest wealth tax rate in Switzerland. In contrast, the other 18 cantons use graduated rate schedules, where the tax rate increases progressively with the level of taxable wealth. However, it’s worth noting that this progression is far less pronounced compared to income tax rates.

Who Benefits from Wealth Tax?

Wealth concentration in Switzerland has increased significantly in recent decades, making it among the highest in the world. Paradoxically, the tax burden on wealth and high incomes has decreased over the past 50 years. This is largely due to Switzerland’s decentralized wealth tax system, where each of the 26 cantons sets its own tax rates and frequently adjusts them to remain competitive.

Historically, wealth taxes have played a crucial role in Swiss public finance. Dating back to the early 18th century, Swiss cantons have relied on wealth taxes as a primary source of income. Even at the federal level, wealth was taxed between 1915 and 1959. Today, wealth tax revenue accounts for 3.8% of total state income, making Switzerland one of the few countries where wealth tax contributes significantly to public finances.

However, despite the presence of a wealth tax, Switzerland continues to attract affluent individuals due to its favorable overall tax environment. While wealth is taxed at the cantonal level, Switzerland has in general no capital gains tax on private securities, allowing individuals to grow their investments tax-free. Additionally, Switzerland’s tax competition between cantons creates flexibility and potentially lower tax burdens, as cantons adjust rates to attract residents and investors. This decentralized system, combined with a high quality of life, political stability, and robust financial infrastructure, makes Switzerland an appealing destination for wealthy individuals seeking both asset growth and financial predictability.

How to Optimize Wealth Tax

In this section, we do not advocate tax evasion. Hiding assets from tax authorities is a risky and inadvisable strategy, as tax authorities are increasingly interconnected with financial institutions worldwide. Concealed assets are likely to be discovered, both in Switzerland and globally, due to the Automatic Exchange of Information (AEOI) system, which facilitates the exchange of financial and fiscal information between tax authorities across numerous countries.

However, there are legitimate ways to optimize wealth tax liabilities while staying fully compliant with the law. Below, we explore three practical and widely accessible strategies for effectively managing tax obligations in Switzerland.

- Residence in a tax-favorable municipality or canton;

- In certain cases, investment in real estate, whether domestic or foreign, may have mild impacts on wealth tax;

- Depending on the specific circumstances, retirement savings can offer modest benefits for wealth tax purposes.