International Work Arrangements in Switzerland

Table of Contents

1. Introduction to working in Switzerland with foreign employers

1.1 Employment vs. Self-Employment

Understanding the distinction between employment and self-employment is essential in the context of international work arrangements, particularly for legal and tax implications.

Defining Employment and Self-Employment

- Employment:

- Employment signifies working in a subordinate position for a determined or indeterminate period without bearing economic risks.

- Key Indicators: Lack of significant investments, working under someone else’s name and account, adherence to directives, binding to work plans and schedules, working regularly for the same employer, and using tools or materials provided by the employer.

- Self-Employment:

- In contract, individuals who operate under their own name, on their own account, are considered self-employed.

- They are in an independent position and bear their own economic risk.

- Key Indicators: Significant investments, possession of business premises, bearing costs and loss risks, employing staff, autonomy in work execution, setting own work hours, and working for multiple clients.

Practical Differences in Employment and Self-Employment

Access to Social Security System:

- Employment:

- Employees are automatically enrolled in social security systems by their employers. Their contributions are typically split between the employer and employee, ensuring coverage for pensions, unemployment, and other benefits.

- The employer is responsible for deducting and remitting these contributions to the relevant authorities and insurance companies.

- Self-Employment:

- Self-employed individuals must independently enroll in and manage their social security contributions.

- They are fully responsible for their own old age insurance, pension planning, and other insurances.

Paying Taxes:

- Employment:

- Swiss residents either file annual tax returns, have their taxes withheld at the source by the employer or both. In any case, the employer provides the necessary salary documentation for any reporting obligations of the employee.

- The employer is responsible for calculating, withholding, and remitting the employee’s income tax to the tax authorities.

- Self-Employment:

- Self-employed individuals are responsible for determining their profit by having a simplified or double-entry bookkeeping system.

- This requires a more comprehensive understanding of the tax system and potentially higher administrative overhead for managing finances.

Legal and Tax Implications

1. Social Security Contributions:

- Employment:

- Employers are responsible for deducting and remitting social security contributions (AHV, IV, EO) for their employees.

- Contributions are usually shared between the employer and the employee.

- Self-Employment:

- Self-employed individuals must independently manage their social security contributions.

- They pay 10% of their assessable income in contributions, with the basis being the net income (revenue-expenses=profit) as assessed for direct federal tax.

2. Benefits Eligibility:

- Both employees and self-employed individuals have identical benefit calculation methods for AHV and IV. This ensures equitable access to social security benefits, regardless of employment status.

3. Tax Deductions and Liabilities:

- Employment:

- Employers can deduct employer contributions made for their employees from their business results.

- Employees benefit from the deduction of employee contributions at source which reduces their net salary which is the ‘starting point’ for their tax calculation (gross salary-employee contributions=net salary).

- Self-Employment:

- Self-employed individuals can fully deduct their AHV/IV/EO contributions as business expenses.

- However, they are responsible for their own contribution calculations and payments.

4. Family Allowances:

- Self-employed individuals are subject to the FamZG and must join a family compensation fund, similar to employers. The benefits and contributions are managed similarly for both employment statuses.

5. Unemployment Insurance:

- Employment:

- Employees are typically covered by unemployment insurance (ALV).

- Self-Employment:

- Self-employed individuals are not connected to ALV and do not have unemployment insurance coverage.

6. Professional Pension (2nd Pillar):

- Employment:

- Employees are generally included in mandatory professional pension plans provided by their employers.

- Self-Employment:

- Self-employed individuals are not subject to mandatory professional pensions but can opt for voluntary insurance.

7. Accident Insurance:

- Employment:

- Employers typically provide accident insurance for their employees.

- Self-Employment:

- Self-employed individuals are not automatically insured against accidents but can opt for voluntary insurance under the UVG.

8. Taxation of Benefits:

- Regardless of employment status, benefits from social security (AHV/IV/EO) are fully taxable upon disbursement.

The Concept of ‘Scheinselbstständigkeit’ (Pseudo Self-Employment)

- Definition and Implications:

- Refers to situations where individuals are classified as self-employed but function under the control of an employer, lacking the social and legal protections of employees.

- Criteria for determining pseudo self-employment include the duration and frequency of collaboration, type of activity, degree of autonomy, and financial relationship between the worker and the employer.

- Consequences for Companies:

- Legal repercussions include the risk of litigation for non-compliance with labor and social security laws, potential fines, back payments of wages or social security contributions, and risks of legal action by pseudo self-employed individuals.

- Consequences for Workers:

- Workers incorrectly classified as self-employed may lose entitlements like social security benefits, face higher contributions, and lack protection in areas such as paid leave and unfair dismissal.

4. Recommendations for Workers and Companies:

It is crucial for both workers and companies to recognize that, in the Swiss context, the lines between employment and self-employment can be quite thin. Relying on assumptions without a thorough assessment of the work relationship could lead to significant risks. In a worst-case scenario, Swiss authorities, such as the cantonal compensation office, might conduct an audit and retroactively classify a self-employed relationship as employment for its entire duration. Such a reclassification can have extensive consequences for both parties involved, encompassing legal and financial ramifications.

1.2 Direct vs. Indirect Employment

In the realm of employment, understanding the legal framework and structure of different employment models is essential. These models primarily fall into two categories: direct and indirect employment.

Direct Employment involves a legal and operational relationship between two parties: the employer and the employee. This model is straightforward; the employer hires, pays, manages, and is legally responsible for the employee. The employer directly oversees work activities, complies with labor laws, and provides benefits. This traditional model offers clarity in roles, responsibilities, and protections under employment law.

Indirect Employment, in contrast, introduces a third party into the relationship. This model typically involves the employee, the end client where the employee works, and an intermediary such as an Employer on Record (EOR), an LLC/LTD of the worker or a subsidiary of the employer. The intermediary handles administrative and legal responsibilities like payroll and compliance, while the end client manages the day-to-day work of the employee. This model can offer flexibility and specialized services but involves more complex legal dynamics due to the involvement of multiple parties.

Understanding Direct and Indirect Employment Models

When considering whether a direct or indirect employment structure is more suitable, particularly in scenarios involving an international context like an employer or end client abroad and a worker and intermediary in Switzerland, various factors and specific areas need to be evaluated. Each structure has its advantages and disadvantages depending on the context.

1. Resolving Disputes:

- Direct Employment:

- Might be simpler in terms of dispute resolution as there are only two parties involved (employer and employee). The legal jurisdiction and applicable laws are generally clear.

- Better for: Situations where clear, direct communication and straightforward legal recourse are preferred.

- Indirect Employment:

- Can be more complex due to the involvement of a third party (intermediary). Disputes might arise about which party (end client or intermediary) is responsible for addressing specific issues.

- Better for: Scenarios where the intermediary has specialized expertise in handling disputes, especially in international contexts.

2. Administering Taxes and Complex Benefits (e.g., Employment Shares/Options):

- Direct Employment:

- More straightforward for administering complex benefits as the employer directly manages these aspects, but more challenging to administer international taxation when workdays in the state of the employer are involved.

- Better for: Situations where benefits like stock options are a significant part of the employment package, requiring direct employer oversight and employments with mostly Swiss workdays.

- Indirect Employment:

- Might be challenging due to the intermediary’s involvement. The intermediary may not be equipped to handle complex benefit schemes, especially if they don’t easily match with benefit schemes outlined by the Swiss tax system. But as the employee would be a Swiss resident with a Swiss employer on paper, there are usually no connectors to foreign taxation.

- Better for: Cases where benefits are standardized or not a major component of the compensation and cases with a larger portion of the work conducted in the state of the end-client (factual employer).

3. Dealing with Authorities in Switzerland:

- Direct Employment:

- Can be more challenging if the employer is abroad and unfamiliar with Swiss employment laws and regulations. Compliance risks could be higher.

- Better for: Employers with a strong understanding of Swiss employment laws or those who can invest in local legal expertise.

- Indirect Employment:

- An intermediary based in Switzerland can be beneficial in ensuring compliance with local laws, handling administrative tasks, and liaising with Swiss authorities.

- Better for: Foreign employers/end clients who need local expertise and support in managing the legal and administrative aspects of employment in Switzerland.

4. Conclusion

When international employers engage workers based in Switzerland, both direct and indirect employment models can be effectively utilized, each offering distinct advantages. The key to success in either model lies in establishing strong partnerships with knowledgeable partners within Switzerland.

- In a direct employment scenario, the international employer can manage their Swiss-based employees effectively by collaborating with local Swiss experts. These professionals can navigate the complexities of Swiss employment laws and tax regulations, ensuring compliance and smooth operation, despite the employer being based abroad.

- In the indirect employment model, utilizing a Swiss-based Employer on Record (EoR) can streamline the employment process. The EoR takes on the legal and administrative responsibilities, acting as a crucial intermediary that bridges the gap between the international employer and the Swiss legal framework.

- For employees who operate through their own business entities, such as LLCs or LTDs, with the end client abroad, as well as for subsidiaries of foreign employers with the purpose of hiring personnel in Switzerland, a competent Swiss accountant is essential, as they are obliged to keep Swiss double-entry bookkeeping.

2. EU-Employments

Context and Setup

Switzerland presents a unique employment setup for EU/EFTA nationals working exclusively in the country for companies based in these areas. This EU-Direct-Employment model is intricately governed by Swiss and EU legal provisions. In these setups, employers often appoint a Swiss representative responsible for managing Swiss payroll documentation, reporting, and acting as a point of contact for the compensation office and insurances.

Art. 21 EU-Direct-Employment Variation

A notable variation of this model exists under Article 21 of EU Regulation 987/2009. In this arrangement, employers may designate the employee themselves as the representative to handle matters with the Swiss compensation office, given there is mutual agreement on this process.

Social Security and Insurance Contributions

Employees under this model are insured in Switzerland, aligning with the Swiss social security system. This integration mandates adherence to the AHVG and compliance with EU Regulation 987/2009. Employers from EU/EFTA states are required to bear half of the social security contributions and ensure parity in their payments to the Swiss compensation office.

Misconception of ANobAG

It is crucial to clarify that in EU-Direct-Employment scenarios, the concept of ANobAG (which translates to ‘employee without a contributing employer’) does not technically apply since the employer is accessed to the Swiss social security system. Despite this, the term ANobAG is regularly erroneously used, even by cantonal authorities, blurring the lines between actual ANobAG situations and EU employments under regulations like EU 987/2009.

Application of Payments and Employer Obligations

The practical application of payments and employer obligations varies significantly based on whether the parties have agreed to Article 21, paragraph 2.

Without Article 21 Agreement:

- Employer’s Role: The employer appoints a local representative in Switzerland, such as Taxolution Advisory LLC, to handle correspondence and billing from Swiss authorities and insurance companies.

- Contribution Payments: This representative is responsible for preparing payroll documents and guiding the employer on various payments, including provisional and final contributions as well as net salary distributions to employees.

- Salary Payments: Employees benefit from this arrangement as it mirrors traditional Swiss employment practices. They receive their net salary without having to manage provisional invoices or budget for contribution payments—this is all handled by the employer with assistance from the representative.

With Article 21 Agreement:

- Employee’s Role: The employee is appointed as the representative, taking on the responsibility for handling all interactions with the Swiss compensation office. This includes the timely submission of social security contributions and managing any required documentation.

- Employer’s Contributions: Employers typically issue gross salaries along with their portion of the contributions directly to the employees. Swiss regulations do not mandate a salary statement from the employer’s home country.

- Payment Flow: Employees receive all invoices directly from compensation offices and insurance providers and must navigate the complex timing of various contributions, potentially seeking support from service providers like Taxolution Advisory LLC. The inconsistency between regular salary payments and the sporadic nature of contribution invoices (which could be billed quarterly, monthly, or annually in advance) can lead to confusion.

Administrative Hurdles:

System Understanding: An advanced understanding of the Swiss social security system is needed to maintain up-to-date and precise reimbursements. Alternatively, the employee might need to advance certain employer contributions, with both parties balancing out after the year-end declarations.

Invoicing Schedule: Depending on the salary, provisional Pillar 1 (OASI) contributions will be invoiced monthly or quarterly. Pension fund (OP) contributions are usually invoiced quarterly, and accident insurance (UI) contributions are invoiced annually in advance.

3. ANobAG

Context and Definition

In Switzerland, the ANobAG status applies to individuals working for employers based outside the EU/EFTA who do not have a legal entity in Switzerland. These employees, known as ANobAG (Arbeitnehmer ohne beitragspflichtigen Arbeitgeber), are responsible for their social security contributions since their employers are not obligated to contribute.

Social Security and Insurance Contributions

ANobAG employees must manage their social security contributions independently, amounting to 8.7% of their salary as per Article 6, Paragraph 1 of the AHVG. They receive their salary from the employer without social security deductions and are required to settle these contributions directly with the Swiss compensation office. This salary, inclusive of any social security contributions paid by the employer, is considered the determining salary for AHV purposes.

Variations in Employer Contributions

There are scenarios where employers, despite not being legally required, choose to contribute to social security:

Employer Voluntarily Pays Contributions:

- If an employer outside the EU/EFTA decides to pay social security contributions, the rate for both employer and employee is 4.35% of the determining salary. In such cases, the employer must reconcile these contributions with the Swiss compensation office as if they were a Swiss-based employer, provided the compensation office allows source taxation by explicit and written confirmation, as is at their discretion.

Employer Pays Contributions Without Reconciliation:

- In situations where the employer pays social security contributions but does not reconcile with the compensation office, such agreements are valid only between the employee and employer, not with the compensation office. The total salary paid to the employee, including these contributions, is considered the determining salary for AHV.

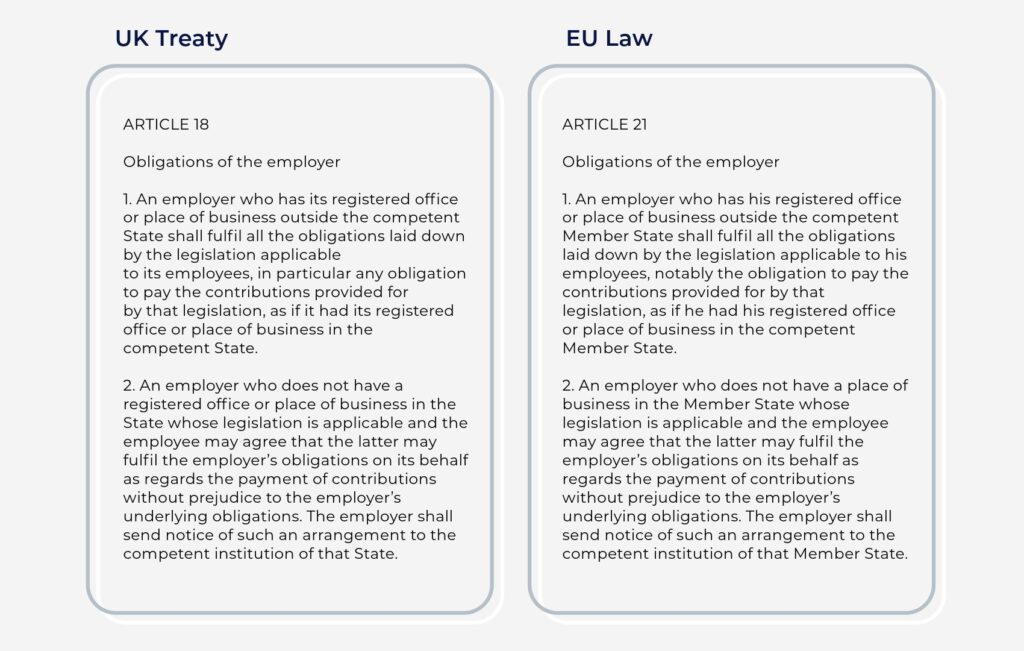

4. UK-Employments Post-Brexit

Legal Background and Unique Position

Given the UK’s departure from the EU, UK employments in Switzerland present a unique situation. According to the Agreement between Switzerland and the UK (0.831.109.367.2), specifically Article 18, paragraphs 1 and 2, the social security responsibilities of employers are aligned closely with those outlined in Article 21 of EU Regulation 987/2009.

CH-UK Social Security Treaty History

1. Transition Period

- January 31, 2020: The UK officially leaves the EU, entering a transition period during which EU law still applies in the UK, including social security coordination under existing EU regulations.

2. Post-Transition Provisional Arrangements

- January 1, 2021: The transition period ends, and EU law ceases to apply in the UK. Switzerland and the UK begin to rely on provisional bilateral agreements to manage their social security coordination.

- January 1, 2021 – September 30, 2021: Provisional arrangements are in place to ensure the continuity of social security coordination between Switzerland and the UK.

3. Bilateral Agreements

New Agreement on Social Security

- November 1, 2021: Switzerland and the UK begin the provisional application of the new Agreement on Social Security Coordination. This agreement aims to secure the long-term coordination of the social security systems of both countries, continuing the framework established under the Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons (FZA).

- October 1, 2023: The new Agreement on Social Security Coordination between Switzerland and the UK comes into full force. This agreement includes the same coordination principles as the FZA, such as equal treatment, determination of applicable legislation, aggregation of insurance periods, benefit export, administrative assistance, and cooperation between authorities and institutions. The provisions of EU coordination law (EU Regulations No. 883/2004 and No. 987/2009) have been simplified and adapted to the needs of the two countries.

Key Agreements and Provisions

October 1, 2021 – October 1, 2023: Provisional Agreement on Social Security Coordination

- Provides a framework for the coordination of social security systems.

- Ensures continuity of social security rights and obligations for individuals moving between Switzerland and the UK.

November 1, 2021 – October 1, 2023: Provisional Application of the New Agreement on Social Security Coordination

- Key Principles:

- Equal treatment.

- Determination of applicable legislation.

- Aggregation of insurance periods.

- Benefit export.

- Administrative assistance and cooperation.

- Simplified and tailored provisions based on EU Regulations No. 883/2004 and No. 987/2009.

October 1, 2023: Full Implementation of the New Agreement on Social Security Coordination

Continues the principles and framework established under the FZA, adapted to the bilateral relationship between Switzerland and the UK.

Ensures long-term coordination of social security systems between Switzerland and the UK.

Employer’s Contribution Obligation

This agreement imposes a mandatory contribution obligation on employers, meaning that the term ‘ANobAG’ does not apply in a legal sense to CH-UK employment relationships. The employer is indeed required to contribute to the Swiss social security system.

Art. 18 Par. 2: Treaty Equivalent of Art. 21 Par. 2 of EU Regulation 987/2009

Article 18, paragraph 2 of the Switzerland-UK agreement is equivalent to Article 21, paragraph 2 of EU Regulation 987/2009. This equivalence ensures that the same application and obligations apply to UK employments as they do for EU employments under the regulation. Specifically, employers can designate the employee themselves as the representative to handle matters with the Swiss compensation office, provided there is mutual agreement on this process.

Application of Payments and Employer Obligations

The practical application of payments and employer obligations varies significantly based on whether the parties have agreed to Article 18, paragraph 2.

Without Article 18 Agreement:

- Employer’s Role: The employer must appoint a third-party representative in Switzerland to administer all interactions with the Swiss social security authorities.

- Contribution Payments: The employer is the direct addressee of all invoices from the Swiss authorities.

- Salary Payments: The employer only needs to pay the net salary to the employee, as the representative handles the calculation and submission of social security contributions.

With Article 18 Agreement:

- Employee’s Role: The employee is appointed as the representative, taking on the responsibility for handling all interactions with the Swiss compensation office. This includes the timely submission of social security contributions and managing any required documentation. It should be noted that if an agreement under Article 18, paragraph 2 is made, it has no effect on liability—the employer and employee remain co-liable for contributions.

- Employer’s Contributions: The employer is still obligated to make their portion of social security contributions. These contributions must be paid directly to the employee.

- Payment Flow:

- The employer calculates the gross salary plus the applicable employer social security contributions.

- The total contribution amount (gross salary plus both employer and employee contributions) is transferred to the employee.

- The employee is responsible for ensuring that the contributions are correctly and promptly paid to the Swiss authorities.

Administrative Hurdles:

- Invoicing Schedule: Depending on the salary, provisional Pillar 1 (OASI) contributions will be invoiced monthly or quarterly, pension fund (OP) contributions are usually invoiced quarterly, and accident insurance (UI) contributions are invoiced annually in advance.

- System Understanding: An advanced understanding of the Swiss social security system is needed to maintain up-to-date and precise reimbursements. Alternatively, the employee might need to advance certain employer contributions, with both parties balancing out after the year-end declarations.

5. Tax Situation of International-Direct-Employees (EU-EFTA/ANobAG/UK Employments)

The tax status of employees with foreign employers is governed separately by local tax laws and the double taxation treaty between Switzerland and the respective EU country. Key principles include:

- Since the employer is not based in Switzerland, withholding taxes are not applicable. Individuals, even with a B permit, are obliged to file tax returns, deviating from the typical withholding tax procedure.

- As tax residents in Switzerland, individuals are taxed on their worldwide income and wealth.

- Foreign workdays may lead to tax allocation where days worked in the employer’s state could be subject to taxation there.

6. Alternative Structures

Establishing a Swiss Company for Employment

In Switzerland, workers have the option to establish their own company, creating a formal employment relationship with a Swiss employer on paper. This structure allows the worker’s business to invoice their services to the end client (actual employer) located abroad. By having a Swiss residence and employer, this model can adeptly navigate complex international issues related to social security and taxes, even if workdays are spent in the state of the end client. The creation of a Swiss business effectively results in the worker establishing their own payroll entity, with the notable distinction being that the company is owned by the worker, unlike in a third-party Employer on Record (EoR) setup.

6.1 Forms of Business Ownership and Legal Implications

When discussing business ownership in this context, it’s essential to refer explicitly to creating a structure with legal personality, such as a Limited Liability Company (LLC) or Limited (LTD). These entities function as Swiss employers. Registering as a sole proprietor is often not feasible (typically due to the single-client scenario) and does not establish the necessary ‘Swiss anchor’ of having a Swiss employer, which is crucial for managing the mentioned international aspects, in case they pose an obstacle in the particular case. Nonetheless, it’s worth noting that in situations where workdays are exclusively within Switzerland and client relationships align with Swiss self-employment criteria, opting for a sole proprietorship can be advantageous. This model offers simplicity and ease of operation, making it an attractive option under the right circumstances, just not necessarily in the context of international work arrangements.

Legal and Financial Considerations

Owning a business in Switzerland involves administrative and financial responsibilities, including compliance with Swiss accounting and reporting obligations. For many, opting for an EoR model may be more comfortable, as it resembles regular Swiss employment where the worker receives a net salary and salary statements, without the administrative burdens.

However, the primary advantage of owning a business, particularly when it functions mainly as a payroll company, lies in financial scaling. When the business reaches a certain revenue threshold, the option of distributing payments through both salaries and dividends becomes a viable tax planning strategy. Dividends can be taxed at reduced rates, although cantonal variations exist. This approach requires careful consideration, as Swiss regulations necessitate that business owners who are actively involved in their company must attain a certain salary level (aligned with industry/position standards) before they can draw dividends. To be more precise, while drawing dividends is possible, it can be contested by social security or tax authorities if deemed inappropriate relative to the salary level.

6.2 Subsidiary in Switzerland

For companies abroad looking to hire in Switzerland, establishing a Swiss subsidiary is a viable option. This method allows employees to be hired directly by the Swiss entity. However, it brings administrative responsibilities, as the subsidiary is subject to the same administrative principles as outlined in the business ownership section. While using an Employer of Record (EoR) might be simpler for payroll purposes, the cost-benefit analysis usually changes with the number of employees. For a single employment, a subsidiary might be less cost-effective compared to an EoR. However, as the number of employees increases, the subsidiary can become more financially advantageous, outweighing the EoR fees.

Establishing and Managing a Swiss Subsidiary

When setting up a subsidiary in Switzerland, businesses can opt for either a LLC or an Ltd. Both legal forms offer the advantage of limited liability. For a LLC, a minimum capital of CHF 20,000 is needed, while an Ltd requires CHF 100,000. Founding a LLC or Ltd involves registering in the Commercial Register and adhering to bookkeeping and audit obligations.

They obliged to keep books and accounts in accordance with the rules defined in the Swiss Code of Obligations (CO 957 ff.). If the company exceeds two of the following thresholds in two consecutive financial years is subject to an ordinary audit (CO 727):

- Balance sheet total: CHF 20 million

- Turnover: CHF 40 million

- Full-time employees: 250

In addition, public companies and companies that are obliged to prepare consolidated financial statements must in any case carry out an ordinary audit. The others are subject to a limited audit. They can also dispense with an audit altogether if they employ fewer than ten people on an annual average.

In the context of this article, it is worth noting that companies in Switzerland are formally required to have a Swiss resident (i.e. a person living in Switzerland) with signing authority.

6.3 Branch in Switzerland

A branch in Switzerland, also known as a Zweigniederlassung, is an extension of a foreign parent company. It’s a commercial enterprise that is legally part of the main company but operates with a degree of independence, including having its own premises and management, performing distinct tasks, and maintaining separate financial statements. However, the branch is not a separate legal entity and does not require minimum capital for establishment.

The branch needs to be registered in the Swiss Commercial Register and must comply with local business regulations, including naming conventions and having authorized representatives in Switzerland.

Operating a Branch in Switzerland for Payroll Purposes

In the context of working under a branch in Switzerland, while the employment is officially with the foreign parent company, the branch assumes significant administrative roles. It functions as an intermediary for Swiss authorities, handling social security and tax payments. The branch is also responsible for managing payroll documentation and processing salary payments. This arrangement merges direct and indirect employment structures, where the legal relationship is with the parent company, as the branch cannot enter an employment without legal personality, but it facilitates key administrative tasks, acting as a transparent third party between the employee and the employer.

For the purpose of hiring personnel in Switzerland, a branch can perform actions on behalf of the parent company abroad, without the formal hurdles a subsidiary would bring.

Comparison with Subsidiary Model

A branch differs from a subsidiary in several key aspects:

- Legal Independence: Unlike a subsidiary, a branch is not a separate legal entity but part of the parent company. Subsidiaries (AG or GmbH) have their legal personality, with liability limited to the entity’s capital.

- Financial and Tax Obligations: Branches do not have separate bookkeeping obligations under Swiss law; this responsibility falls on the main company. However, for financial control, branches often independently perform balance sheet and profit and loss accounting. Subsidiaries must adhere to Swiss accounting and reporting regulations.

- Setup: Establishing a branch can have lower initial costs, as there’s no minimum capital requirement.

- Strategic Considerations: Subsidiaries provide a higher degree of operational flexibility and legal separation, which can be advantageous for risk management and capital investment strategies. Branches, on the other hand, offer a simpler extension of the parent company’s operations in Switzerland, without the complexity of managing a separate entity.